New York City will soon be getting its own personal offshore wind farm. The Empire Wind 1 project just received a US$3 billion project financing package and is expected to go online in 2027, powering roughly half a million borough residents. But what’s the catch?

In the energy sector, levelized cost of energy (LCoE) is a key metric that looks at the cost of electricity generated over the lifetime of the unit generating the power. LCoE takes into consideration everything from operational costs to construction, fuel (if applicable), maintenance, output, right down to finance costs and interest payments on loans.

Using LCoE, you can make an apples-to-apples cost comparison between all methods of electricity generation. For example, you could see that utility-scale solar and land-based wind power projects average around $20-50/MWh while Natural gas fired plants come in around $45-80/MWh, et cetera.

As of 2023, the global average LCoE of offshore wind farms was right around $75 per megawatt-hour. China spends around $65.7/MWh while the UK spends a bit less at roughly $50/MWh. Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands all have an LCoE of about $84/MWh.

The United States pays a bit of a premium compared to the rest of the world, at around $89.33/MWh.

NYC’s new clean energy project will cost significantly more.

Equinor, the developer behind Empire Wind 1, secured an 80,000-acre (32,375-ha) lease located 15 miles (24 km) southeast of Long Island. Along with the lease, the company locked in a contract with the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority to deliver power at a strike price of $155 per megawatt-hour over the next 25 years – nearly double the national average, and roughly the typical 20 to 25-year life expectancy for a sea-faring wind turbine. High winds, constant motion from waves, and harsh saltwater corrosion are the leading causes of shortened shelf life.

There’s a price to pay for sustainability.

Luca Bravo

While that’s a fantastic deal if you’re an Equinor executive, the financial impact on those living in NYC where the wind energy will be directed is negligible … but it’s a start.

A turbine-laden 80,000-acre plot of Atlantic Ocean – which is nearly half the size of NYC – could generate 810 MW if running efficiently at its designed capacity. That is around 3.19 TWh per year or roughly 6% of NYC’s overall consumption. Empire Wind 1 will be the first offshore wind project to connect directly to NYC’s electrical grid.

As of writing, residents of the Big Apple are paying Con Edison about $0.31 per kilowatt-hour of electricity. Under optimal conditions, and at $155/MWh ($0.15/KWh), Empire Wind 1 could theoretically bring the overall cost of electricity down to 30.1 cents, but don’t hold your breath on that being passed onto customers.

NYC, the “city that never sleeps,” consumes around 53 terawatt-hours per year overall, more than any other city in the USA – that’s according to the most recent city-level data we can find, which is remarkably from 2015-16. Even Las Vegas, the city that only sleeps during daylight hours, only uses 25-30 TWh per year to keep its casinos lit and one-armed bandits raking in the dough.

New York’s Indian Point nuclear plant provided about a quarter of NYC and Westchester County’s electricity before its reactors were taken offline over the last few years. Since then, natural gas-fired power plants have kicked into overdrive to fill the power gap, including the aging natural gas-fired Ravenswood generation station and the Astoria gas-or-diesel-fired power plant. Both are located in Queens, and combined they account for roughly 28% of the city’s electrical needs. Both have raised concerns about pollution and greenhouse gases.

Equinor

The use of offshore wind energy will supplement the existing grid while also offsetting CO2 emissions … but at the cost of affecting the marine ecosystem. Offshore wind farms have been known to disrupt marine life in a variety of ways, but have also acted as a sort of refuge for sea creatures, as they’re generally restricted from commercial fishing – which also presents its own problems like over-predation.

The US has been a slow adopter of offshore wind technology, mostly due to regulatory hurdles, higher costs, and cheaper sources like natural gas. There are only three currently in operation. As the infrastructure grows, the LCoE of future projects should, theoretically, go down over time.

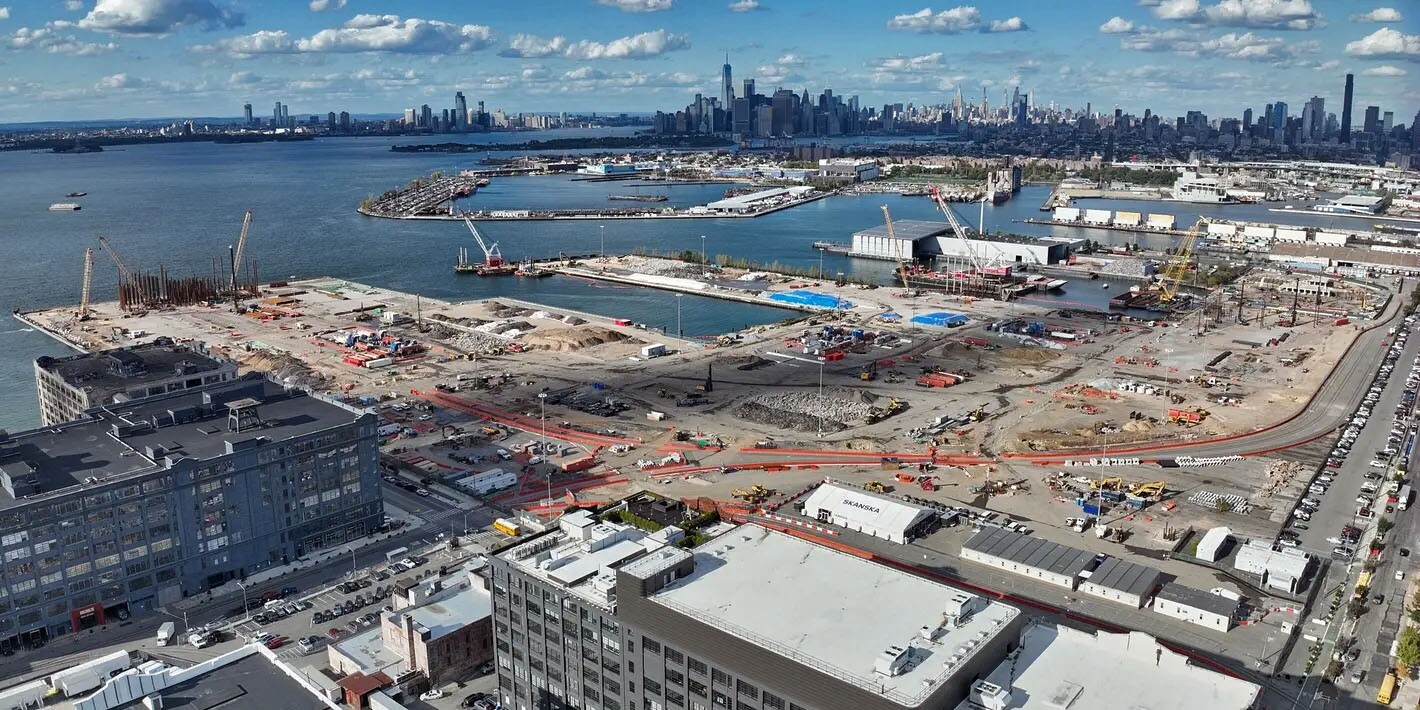

In the meantime, Equinor will be creating more than a thousand union jobs for the redevelopment of the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal and the construction of wind turbines until the project goes online in 2027.

Source: Equinor